Coastal populations everywhere are at risk from tsunami waves that can strike quickly with little warning.

On February 06, 2013 an 8.0-magnitude undersea earthquake struck roughly 20 miles of the coast of the Santa Cruz group in Temotu Province, Solomon Islands. Minutes later a tsunami warning was issued and, quickly following, villages in the Temotu province were hit by a tsunami wave. The wave destroyed homes and food crops, leaving 10 dead and thousands affected. Numerous aftershocks followed, along with poor weather and heavy rain. Water supplies, airstrips, and wharves were damaged – the possibility of landslides increased and conditions hampered the movement of humanitarian aid. The Solomon Islands government declared the Temotu province a disaster area.

The Santa Cruz tsunami is an example of a rapid onset hazard: the population was struck quickly and received very little or no warning. The nature of this type of impact requires communities to work towards hazard preparedness and mitigation that increases awareness of how quickly a disaster can develop and how to respond when an event occurs. This focus is particularly relevant as increasing urban populations in coastal areas expose higher numbers of people to the dangers of rapid onset hazards.

It is important to remember that if you are near the coast and feel the ground shake, see the ocean water receding, or hear a loud roar, you should head to high ground immediately. A locally generated tsunami could arrive within minutes. Either run up hills and away from the coastlines, or if the coastal area is flat, perform a vertical evacuation. A vertical evacuation means finding a tall but strong structure, such as a high-rise building, and try to reach the fifth floor. On land, going up to 70 feet (about 23 meters) above sea level is usually sufficient.

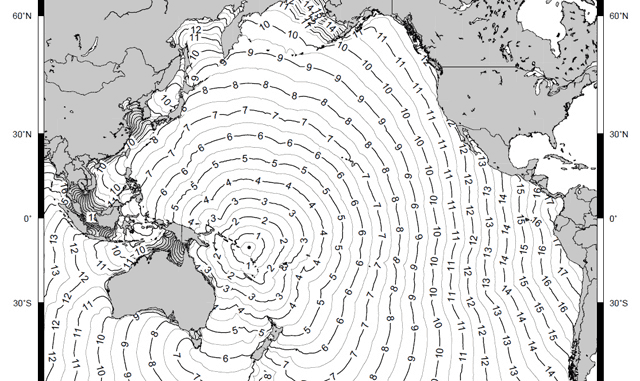

However, not all tsunamis are locally generated and once a hazard (like an undersea earthquake) is detected, estimates can be made about the arrival of the first tsunami waves. The amount of time before the arrival depends on the distance between any location and the epicenter of the event causing the tsunami. The farther a location is from the epicenter, the longer it takes for the waves to arrive. The waves travel at about jet speed (up to 500 miles/hour) in the open ocean. Tsunami travel time can vary from a few minutes up to 14-15 hours or more.

Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) offers a wide range of information that can be used to help prepare for a tsunami, including tools for risk assessment and early warning. General information is available on the PDC website, and the PDC DisasterAWARE platform provides comprehensive hazard monitoring available to the public through the Global Hazards Atlas. The PDC mobile app, Disaster Alert, provides near real-time hazard notification for iOS or Android devices. (See download information below.)

Additionally, PDC offers informational kits that help promote tsunami awareness and preparedness. The kits can include maps, booklets, pamphlets, posters, and presentation materials, as well as instructions for use along with strategies for the implementation of tsunami awareness outreach programs. Tsunami awareness kits can be customized upon request for any coastal location or audience, and made available in a variety of formats. To view a selection of tsunami resources available via the web, visit: http://tap.pdc.org. For more information on customized tsunami awareness kits, address your request to info@pdc.org.

For more about the Santa Cruz, Solomon Islands Tsunami:

• For documents and reports, see Pacific Disaster Net (PDN).

• Additional reports and links are found at the GLIDE site.

For more about DisasterAWARE:

• For details, see the DisasterAWARE documentation.

• Do-it-yourself training to become a proficient user of Atlas.

• Watch the new DMRS video on YouTube.

To keep yourself up-to-the-minute about hazards and disasters:

• Download the free PDC Disaster Alert mobile app for your iOS and Android devices,

• Follow us on Twitter and Facebook (/DisasterAWARE), and

• Use PDC’s Global Hazards Atlas from any computer.

For the latest Weather and Disaster News, use the PDC Weather Wall.

While you are thinking of hazards, think of preparedness. PDC provides disaster preparedness information, including printable instructions for assembling a Disaster Supply Kit and rehearsing a Family Disaster Plan.

About PDC:

Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) envisions a safer, more secure world—where populations live in safer, more disaster-resilient communities informed by science and technology, and equipped with sound decision support tools. To help make that vision a reality, PDC is dedicated to supporting disaster risk reduction (DRR) efforts by providing evidence-based information and applications to the public and disaster managers worldwide. PDC, a program managed by the University of Hawai‘i, was established by the U.S. government in 1996.